Following Deckard’s response to Occupy.com, this is the second in a series of posts to be featured on Permanent Crisis offering an in-depth examination of the possibilities for a new, internationally-oriented left politics. It is prompted by the conviction that some kind of internationalist stance must again become available on the left if the idea of a post-capitalist society is to cease to seem a mere chimera, and instead to once again appear as a live option to the multitudes currently being crushed beneath the weight of a global regime of austerity. It is also prompted by the sense that any purportedly radical politics, if it is to live up to its name, must realize that its defeat is already sealed so long as it ultimately remains limited, in its theory and practice, to the horizon of the nation-state. The unprecedented global reach and international mobility of capital in the post-Fordist era demands the formulation of a similarly global vision on the left that is rooted in the historical reality of the current moment, most notably in the protracted social devastation unfolding in the form of the general crisis of neoliberal capitalism.

Notwithstanding the way that pitifully anemic job growth is trumpeted by the liberal press as a sign of imminent recovery, the ultimate outcome of the crisis remains uncertain. In the meantime we are faced with the tacit, slow-motion brutality of generalized austerity. This is steadily converting the neoliberal state into the “austerity state,” a historical bloc in which the horizon of political possibilities is steadily narrowed by an increasingly pronounced, newfound obsession with reducing debts and deficits at all costs. If Dick Cheney’s statement that “deficits don’t matter” accurately encapsulates the inflationary mindset of the political class during the Bush years, the contemporary fixation on deficit and debt reduction – embodied in its purest form by something like Rand Paul – represents the new, post-crisis gospel of austerity. What was that thing Marx said about capitalism beating dialectics into the heads of the bourgeoisie?

The fact that the movement of capitalist society is full of contradictions impresses itself most strikingly on the practical bourgeois in the changes of the periodic cycle through which modern industry passes, the summit of which is the general crisis...the intensity of its impact will drum dialectics even into the heads of the upstarts in charge of the new Holy Prussian-German Empire” (Preface to the Second Edition of Capital)....or the Holy American Empire, as the case may be.

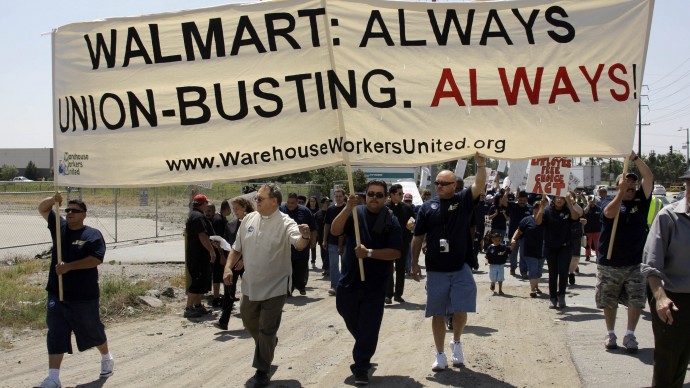

In any case, it is upon this inhospitable terrain that the left needs to somehow begin thinking in international terms. Of course, such a project remains abstract and idealist without roots in currently unfolding practices and organizational initiatives. Fortunately, as of late there has been a rather significant burst of creativity in organizing theory and practice around Walmart Inc., that undisputed conqueror and commercial overlord of U.S. suburbia, that has succeeded in bringing to light some key pressure points within the supply chains of the global giant. It has also brought to the table fresh ideas about advocating and agitating for workers’ collective rights, in the process raising important questions about what union organizing today might look like. At the same time, recent high-profile events, such as the Black Friday walkouts in the U.S. last fall, have evinced some of the apparent limits of these emerging strategies. In light of this, it might be helpful to take a step back and try to reflectively assess their relative strengths, weaknesses, and the possible paths forward.

Walmart, as is generally known, is the single largest private employer of underpaid, brazenly exploited labor in the world. Its empire of sweatshop-produced, cheap retail goods directly employs 2.2 million people and has almost 9,000 stores worldwide; the workforce it indirectly employs throughout the various subcontracted segments of its global supply chain is undoubtedly much higher. As is also common knowledge, the company’s trademark “low prices” are the direct expression of programmatic wage repression throughout its massive workforce, as well as those of its various suppliers in the warehouses that distribute its goods and the factories that produce them. It has pioneered a very clever business model in which the company provides very little to no health benefits at all for its workforce, who then are forced to look to federal and state programs for basic health services and income supplementation. The repression of wages below bare subsistence levels and the effective absence of meaningful health benefits creates a business model, doubtless admired by MBAs everywhere, in which the public essentially subsidizes the wages of Walmart employees.

Of course, the company can only get away with this because it has honed pre-emptive union busting down to a science: fire at the first sign of union activity or pro-union sentiment; deal with the (unlikely) legal consequences, if any, later. Naturally, there usually are no consequences of any import. Thus, Walmart has effectively demonstrated certain key advantages of operating in a country with utterly feckless labor laws that are, often enough, even outright anti-worker. As Josh Eidelson reports at The Nation:

Even though Walmart employs just under 1 percent of the American workforce, most of us live in the Walmart economy. Its model has been forced on contractors and suppliers, adopted by competitors and mimicked across industries. That model includes a relentless squeeze on labor costs. In the United States, workers say they often skip lunch to get by on paltry wages. In Bangladesh, where in late November 112 workers died in a factory without outdoor fire escapes, NGOs blame Walmart for pushing deadly shortcuts.As a result, and as has been well documented, the company has successfully “Walmartized” its competition in the retail and service economy, setting an inspiring example for other businesses: you too can achieve success by impoverishing your employees with below-subsistence wages, no benefits, and the bare minimum of occupational safety provisions, and if anyone sticks their head up to protest, sack ’em and hire someone else desperately looking for work. “Fire and forget,” as Sam Walton probably said at one point.

All

this makes organizing this multinational conglomerate quite a tricky

business. Over the course of the last half-century, Walmart has

generated an impressive record of defeating union drives before they

even begin. An organizing drive by the Teamsters was warded off

during the 1980s by raising the wages of truck-drivers. In 2000, and

in what remains the sole instance of a union actually winning

recognition at a Walmart store, the United Food and Commercial

Workers succeeded in organizing 10 meat cutters in a store in Texas

only to have the company sack

every human in that department across 180 of its stores,

replacing them with subcontracted pre-cut, pre-packaged meats. They

have even closed an

entire store to stave off union presence. Such tactics

demonstrate the draconian lengths to which the company will go in order to

fend off unions at all costs, even incurring significant short-term

financial losses in order to keep them out. Being the third-largest

company in the world allows you to do that. Additionally, and as in

the rest of the food service and retail economy, the abysmal working

conditions, sub-full time hours, and the precarity of a wholly

non-unionized workforce leads to incredibly high levels of turnover

among employees, further complicating traditional organizing methods.

All

this makes organizing this multinational conglomerate quite a tricky

business. Over the course of the last half-century, Walmart has

generated an impressive record of defeating union drives before they

even begin. An organizing drive by the Teamsters was warded off

during the 1980s by raising the wages of truck-drivers. In 2000, and

in what remains the sole instance of a union actually winning

recognition at a Walmart store, the United Food and Commercial

Workers succeeded in organizing 10 meat cutters in a store in Texas

only to have the company sack

every human in that department across 180 of its stores,

replacing them with subcontracted pre-cut, pre-packaged meats. They

have even closed an

entire store to stave off union presence. Such tactics

demonstrate the draconian lengths to which the company will go in order to

fend off unions at all costs, even incurring significant short-term

financial losses in order to keep them out. Being the third-largest

company in the world allows you to do that. Additionally, and as in

the rest of the food service and retail economy, the abysmal working

conditions, sub-full time hours, and the precarity of a wholly

non-unionized workforce leads to incredibly high levels of turnover

among employees, further complicating traditional organizing methods.Such has been the state of affairs for some time at the world’s largest private employer. However, 2012 saw some interesting and highly publicized developments on this front: in the summer, workers in one of the company’s seafood suppliers in Louisiana struck against wage theft and management intimidation and won, winning the backpay owed to them; then, in the early fall, warehouse workers associated – but, importantly, not officially affiliated – with Change to Win and the United Electrical Workers struck in southern California and central Illinois over management intimidation, retaliation, dangerous working conditions, and wage theft. These workers, too, won significant victories, gaining an end to workplace retaliation and obtaining strike backpay in Illinois. They also won a court verdict naming Walmart as a defendant in a class action lawsuit in California, effectively reinforcing workers’ arguments that Walmart is indeed responsible for the working conditions at its suppliers’ facilities. Then, the Organization United for Respect at Walmart caught headlines last Thanksgiving with a series of high-profile actions on and around “Black Friday,” the biggest shopping day of the year when Walmart workers are sometimes stampeded to death by crazed, shrieking mobs of shoppers. While the turnout for these walkouts varied greatly, ranging between from just one or two employees at a store to several dozen at others, the result was a highly publicized event that put OUR Walmart in the national spotlight, as well as Walmart itself. This meant that the company couldn’t follow its usual practice of simply firing anyone whom it remotely suspects of pro-union sentiment, since they were very much in the public eye. As a result, to this date very few of the workers who walked out last November have been fired, though they have certainly been threatened and told not to do it again.

“Open Source Organizing”: Old Tactics, New Forms

These may seem like a handful of isolated, relatively small gains, but they do outline an emerging trend: working people across the United States are slowly coming to the realization that this corporate behemoth, this pure distillation of everything horrendous about the neoliberal global economy, can be opposed and tactically engaged with some measure of success. This is pretty significant considering this is Walmart we’re talking about here.

Underlying

many of the actions taken by OUR Walmart workers and allies over the

last year or so is an experimental organizing model that some are

referring to as “open-source

organizing.” While the organization is financially supported

by the United Food and Commercial Workers, OUR Walmart is more of an

informal association that has explicitly avoided following the

orthodox route of a traditional union drive. The group doubtless

hopes to avoid some of the treacherous, cut-throat retaliation for

which the company is so famous, and perhaps it is also giving up on a

chronically comatose National Labor Relations Board, now rendered even more comatose thanks to

a recent federal court decision, applauded by a variety of right-wing

apparatchiks, nullifying

all but one of its sitting members. But moving outside the

established paths of union organization, election, and certification

also imparts a certain flexibility to the project that is unavailable

in conventional drives to win representation through

majority endorsement on a shop-by-shop basis. While not giving up on the

project of winning formal recognition, OUR Walmart and its allies are

sidestepping the rigid constraints of U.S. labor law, tilted towards

employers as it is, and taking matters into their own hands. Rather

than focusing on the uphill battle of winning exclusive majorities

within single shops, they are attempting to build a more open

movement that aims at providing the knowledge, resources, and support

for workers to take action against Walmart wherever they are and

however they see fit. In other words the group is trying to reinvent,

on a mass scale, what back in the day used to be called “minority

unionism,” or sometimes “solidarity unionism,” in a form

that would be genuinely capable of challenging neoliberal corporate

power.

Underlying

many of the actions taken by OUR Walmart workers and allies over the

last year or so is an experimental organizing model that some are

referring to as “open-source

organizing.” While the organization is financially supported

by the United Food and Commercial Workers, OUR Walmart is more of an

informal association that has explicitly avoided following the

orthodox route of a traditional union drive. The group doubtless

hopes to avoid some of the treacherous, cut-throat retaliation for

which the company is so famous, and perhaps it is also giving up on a

chronically comatose National Labor Relations Board, now rendered even more comatose thanks to

a recent federal court decision, applauded by a variety of right-wing

apparatchiks, nullifying

all but one of its sitting members. But moving outside the

established paths of union organization, election, and certification

also imparts a certain flexibility to the project that is unavailable

in conventional drives to win representation through

majority endorsement on a shop-by-shop basis. While not giving up on the

project of winning formal recognition, OUR Walmart and its allies are

sidestepping the rigid constraints of U.S. labor law, tilted towards

employers as it is, and taking matters into their own hands. Rather

than focusing on the uphill battle of winning exclusive majorities

within single shops, they are attempting to build a more open

movement that aims at providing the knowledge, resources, and support

for workers to take action against Walmart wherever they are and

however they see fit. In other words the group is trying to reinvent,

on a mass scale, what back in the day used to be called “minority

unionism,” or sometimes “solidarity unionism,” in a form

that would be genuinely capable of challenging neoliberal corporate

power.I’ve written before about how the general depredation inflicted upon the labor movement and the working class under neoliberalism is actually generating weird shifts in consciousness towards a more militant stance, including changes in the nature of strike tactics themselves. Well, one of the unique attributes of the open-source or minority model is how it allows for the introduction of a strike-first strategy. The strike ceases to be something that can only happen after much internal deliberation, failed negotations with an employer, and a successful authorizing vote within a union, and even then only according to terms laid down in a contract, and instead becomes a much more spontaneous, free-wheeling affair. This can take the form of a long-planned, highly publicized action, such as the national walkouts on Black Friday of last year, or it can be a kind of surprise attack on the bosses, as a large bloc of food-service workers is demonstrating in New York. This significantly increases the temporal and spatial flexibility of the strike, as the open organizing model allows for nationally coordinated actions with hundreds, or perhaps, eventually, thousands of workers, none of whom are part of a majority in their respective workplaces but who are willing to strike nevertheless. It also allows for the potential to plan and execute walkouts on relatively short notice and without having to deal with the bureaucratic inertia of formal union structures. Such shifts in the form of the strike work in practice to empower the rank-and-file, as workers themselves determine its aims, tactics, and duration, rather than allowing these things to be decided by a contract, by top union bureaucrats, or by a body of federal labor law that has been thoroughly molded in the image of capital.

Another important feature of the open-source model is the potential for broader public involvement. Many thousands turned out to demonstrate against Walmart last Thanksgiving, but only a fraction of those protesters were actually Walmart employees; the vast majority were supporters and allies from the broader communities that are negatively affected in various ways by the corporate behemoth. Again, the absence of contractual limitations means that the demands that motivate a strike or walkout can be articulated in a very broad manner and in a way that enlists a much wider audience of stakeholders than just the union membership. We saw this late last summer with the Chicago Teachers Union strike as well. Although it was a contractually regulated strike, and the C.T.U. was “officially” on strike over negotiable contract items like wage tiers, the C.T.U. consciously and very successfully framed the strike as part of a broader public fight against the attempt to privatize public education in order to service fiscal austerity. Similarly, OUR Walmart and its affiliates – e.g., “Making Change at Walmart” – frame their fightback as part of a much larger vision that implicates the wellbeing of society as a whole in the outcome of their struggle (“Change Walmart and Rebuild America!”). For the campaign, this fight isn’t just about making Walmart a better place to work; it’s about using the fight at Walmart to de-Walmartize America. This framing strategy for mass job actions has the potential to catalyze a formidable political subject around a very broad set of demands, as the evidence steadily accumulates regarding the company’s odious labor practices, its utter contempt for its workers, and the generally debilitating effects it exerts on work standards across the globe.

Such qualities as these tentatively suggest a decentralized horizontalism in the new organizing models that are emerging in retail and service work. These models eschew the bureaucratic structures and tedium of orthodox U.S. unionism in favor of something decidedly more flexible and adaptable, and indeed, potentially much more radical. This strategy meets the company’s “flexibilization” of their workforce with a certain flexibility of its own. Additionally, it makes a lot of sense in the present abysmal state of the labor market, as it uses protests and various spontaneous job actions as means for workers to reacquire their jobs after they have been unfairly fired. This can go a long way toward shoring up the confidence to strike and take direct action in a time when many people are fearful of losing whatever employment they do have.

This horizontalism is the strategy’s greatest strength as well as its greatest weakness, as it attempts to substitute spatial and temporal dynamism for concentrated numbers in a given shop or cluster of shops – the classic method for shutting down production and the conventional means for building union power. This translates into an increase in the necessity of using media publicity to further goals – shaming the company, enlisting the support and sympathy of the broader public, etc. – and a corresponding drop in solid, binding bargaining leverage with the company. But such seems to be the organizing model that makes the most sense for this historical moment in this particular industry, and OUR Walmart is running with it.

The workers in the campaign have also voiced support for the National Garment Workers Federation of Bangladesh, a key supplier of the ultra-exploited, unsafe, cheap labor that makes Walmart’s infamous low-prices possible. It doesn’t seem like anyone is ready to go on strike for workers in another country yet, but there is a nascent sense of solidarity there that recognizes how workers at retail stores here are part of the same supply chain with textile producers on the other side of the world. The “Walmart at 50” media campaign even features a demand directed at Walmart to elevate global living standards by legally establishing a living wage, real occupational safety measures, and basic labor rights for all their contractors and subcontractors. Such demands are part of what is only a nascent movement right now, but they do represent the re-emergence, however tentatively, of a certain international perspective within U.S. labor struggles. Time will tell what direction this goes in, but in the meantime we can plan on showing up to demonstrations and walkouts to show our support of these workers when they take on the improbable task of attempting to civilize the world’s most cutthroat, barbaric multinational corporation.

No comments:

Post a Comment